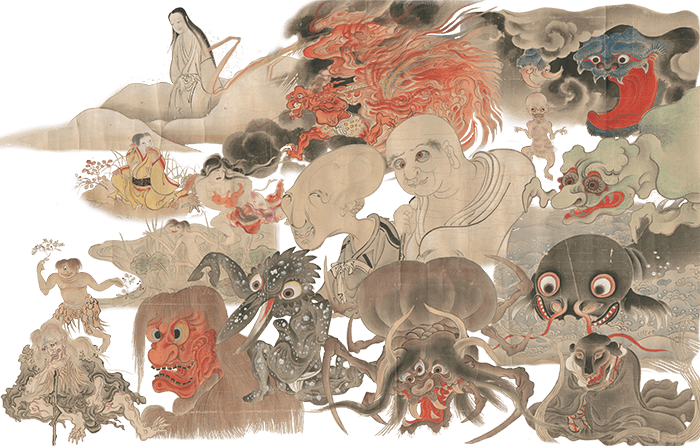

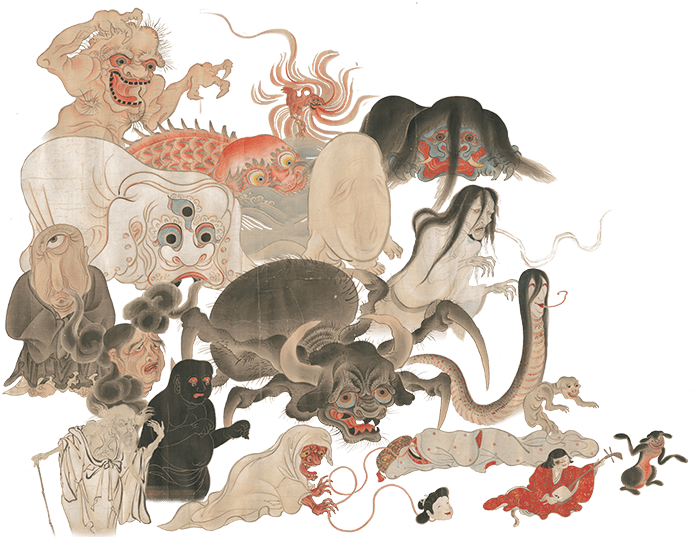

The variety and abundance of bakemono 化物, or yōkai 妖怪 (supernatural creatures and phenomena), in Japanese culture is astounding. For more than a millennium creepy creatures and ghastly ghosts have haunted and entertained the imagination of the Japanese, some familiar, widespread, and longstanding, and some new, localized, and mutable. A post-war boom in yōkai culture, fueled by Japanese horror cinema and the immensely popular manga (comic book) series GeGeGe no Kitarō ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 (1965-1997), by Mizuki Shigeru 水木しげる (1922-2015), led to resurging interest in the history of the supernatural in Japan. Books from before the modern era have been mined for information, both textual and visual, on the historical roots of many supernatural creatures. Toriyama Sekien’s 鳥山石燕 (1712-1788) four-part series of books, Gazu hyakki yagyō画図百鬼夜行 (The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons, 1776-1781) became the most influential source for yōkai information. Much of the information and many of the images Toriyama featured were gathered from earlier sources, such as illustrated handscrolls of the Edo period (1600-1868). From early in the Edo period, handscrolls featuring compendia of supernatural creatures were produced and called Bakemonozukushie (“indexes of bakemono”). BYU’s Bakemono no e 化物之繪 (Illustrations of Supernatural Creatures), also titled Bakemonozukushie 化物尽繪 (Illustrated Index of Supernatural Creatures), is perhaps the oldest extant version of this type of index handscroll.

Bakemono no e depicts thirty-five bakemono from Japanese folklore, hand-painted on paper in vivid color pigments accented with gold and silver pigments. Along with the liberal use of gold pigment and the very high quality rendering of the figures, the scroll’s size (44 x 1525 cm), much taller than most handscrolls, which are usually about 30 cm in height, indicates that it was likely produced for an elite patron. Each figure is labeled with its name in hand-brushed ink. There is no other writing on the scroll, no colophon, and no artist’s signature or seal. Its title comes from a hand-brushed ink inscription on the lid of the wooden box that houses the scroll. An alternate title, Bakemonozukushie, appears on a paper label glued to the side of the box which is likely newer than the inscription on the lid. This label also includes the term koga 古画, meaning “old painting.”

Bakemono no e is held by the L. Tom Perry Special Collections of the Harold B. Lee Library at BYU. It is part of the Harry F. Bruning Collection. Bruning (1886-1975) was an attorney and businessman who collected Americana and Japanese rare books and manuscripts, many of which were purchased by the Lee Library in 1965. Bruning acquired Bakemono no e from Charles E. Tuttle Rare Books in 1952. According to the description in Tuttle’s catalog 266 (October 1952), item 361, “Giant Water Color Scroll of Japanese Spooks,” Bakemono no e was produced c. 1660. This would pre-date the currently oldest known version of a bakemono index scroll, Sawaki Sūshi’s 佐脇嵩之 (1707-1772) Hyakkai zukan 百怪図巻 (The Illustrated Volume of a Hundred Demons, 1737), by several decades.

In 2007, scholar Lawrence Marceau of The University of Auckland, after viewing Bakemono no e at BYU, shared digital images of the scroll with Yumoto Kōichi 湯本豪一, then curator at the Kawasaki City Museum. Yumoto holds Japan’s largest collection of yōkai-related materials. A museum housing the Yumoto collection was opened in Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture, in April, 2019. Yumoto was surprised to find an image of a three-eyed bakemono clearly labeled “nurikabe” ぬりかべ in the BYU scroll that matched an unlabeled illustration of the same figure in a scroll Yumoto owns. Yumoto introduced the nurikabe image to other yōkai scholars and the manga artist Mizuki Shigeru.

Nurikabe, which means “painted wall,” is an inexplicable phenomenon that impedes a traveler’s progress as if it were an invisible wall. Until Japanese scholars were introduced to the Bakemono no e scroll, it was thought that nurikabe had not been illustrated before the modern era. Folklorist Yanagita Kunio 柳田國男 (1875-1962) had recorded oral traditions concerning nurikabe in Fukuoka prefecture on the island of Kyushu and published his findings in 1933. Mizuki based his illustration of nurikabe in GeGeGe no Kitarō on Yanagita’s description, and was surprised and pleased when he found out that nurikabe had indeed been illustrated in the Edo period, stating that Bakemono no e is an “important yōkai national treasure.” Some Japanese scholars, however, contend that the nurikabe illustrated in Bakemono no e and the nurikabe of folklore in Kyushu are not the same. The discovery of BYU’s nurikabe and the subsequent debate over its relationship to the nurikabe of folklore were featured in Japanese newspaper and scholarly journal articles.

One important result of the discovery of BYU’s scroll was the spread of the nurikabe image around the world. After 2007, the visual landscape of nurikabe was dramatically transformed. Though Mizuki had depicted nurikabe as a flat, square wall with short arms and legs, two small eyes and a narrow mouth, nurikabe in Bakemono no e is an elaborately conceived white dog-elephant-like creature with three eyes and black fangs. After its appearance in an Asahi newspaper article, a photograph of BYU’s nurikabe made its way across the world wide web, inspiring new interpretations of nurikabe in art, comic books, animation, and a variety of other formats, including an appearance as an enemy combatant in the long-running Power Rangers television series. Today, both the Mizuki nurikabe and the Bakemono no e nurikabe occupy the shared visual space of this folklore phenomenon, demonstrating the continued mutability of image, taxonomy, and meaning in Japanese yōkai culture.